Ferrogrão - a new train for the Brazilian agribusiness

Cultivation of the protein crop soy is essential for European livestock farming.

A thousand kilometer railway line is intended to make industrial soy production in Brazil cheaper and increase exports. As the second largest buyer of Brazilian soy, the European Union is already partly responsible for the social and ecological damage caused by soy production and for the expansion of cattle pastures in forest areas. Brazil's indigenous population are resisting the construction, pointing to the disregard of their rights and the threat to the climate and biodiversity.

Pictures of fires and deforestation in the Amazon region have been going around the world for years. The increasing loss of forests is exacerbating climate change and the decline in biodiversity. The original vegetation is being cleared to produce soy and beef - also exported to the European Union (EU). The big questions this raises are: What policy instruments are needed to ensure that the EU in its agricultural supply chains protects, rather than endangers areas of high socio-ecological importance like the Amazon rainforest? How can the protection of indigenous rights be ensured in the process?

To find helpful answers for our work, we need expertise from the region. That is why we have been interviewing various experts from the South American countries Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay, but also from the EU - among them scientists, political advisors and human rights activists. Often the difficult political situation in Brazil has been discussed. The government of right-wing conservative President Jair Bolsonaro is increasingly undermining the rights of indigenous and traditional communities for the benefit of the agribusiness lobby. This is done through legislative changes to simplify approval procedures for large-scale projects or to reduce boundaries of protected areas, as well as through the institutional weakening of Brazil's environmental authorities and the Agency for the Concerns of the Indigenous People of Brazil (FUNAI).

Brazil's indigenous peoples make a stand

For three weeks at the end of August of 2021, around 6,000 people from over 170 Brazilian ethnic groups camped in front of government buildings in the capital Brasília to protest for their land rights and against Bolsonaro's anti-indigenous agenda. They protested against several bills that are currently being voted on at the national level. The laws would allow mining in indigenous protected areas and empower the state to retroactively legalise illegal land grabbbing that occurred until 2014 by agribusiness. Furthermore, indigenous peoples could lose their claim to their territories if they could not prove that they were there on the effective date of the Brazilian Constitution in 1988. Thus, indigenous and traditional communities that had already been displaced or forcibly relocated at that time would have no legal claim to their people's territory. To avoid all this - and to protect the rights of indigenous and traditional people as well as the environment - according to our interview partners, greater international attention and economic pressure is needed, especially from the EU, as Brazil's essential trading partner. This could also put a stop to the highly controversial infrastructure project, the almost 1,000 kilometer EF-170 railway line.

933 kilometers of steel through protected areas

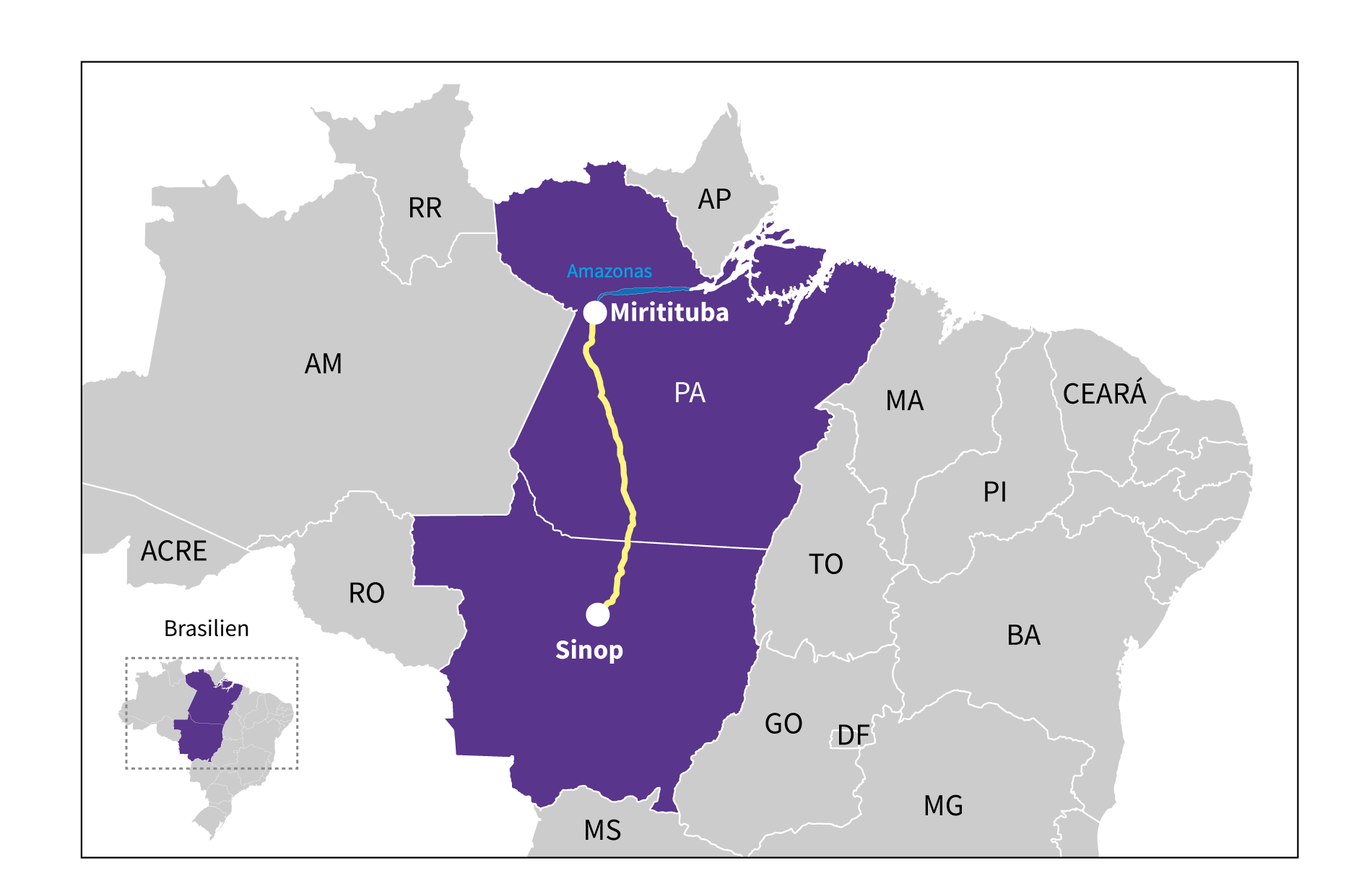

The railway line, popularly known as "ferrogrão" (ferro=iron, grão=grain, i.e. railway tracks for grain), is a nine-year-old strategic project of the largest multinational agribusinesses that dominate trade in Brazil: Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), Amaggi, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus. The planned railway line will connect the country's largest grain growing area, located in the middle of Brazil in the state of Mato Grosso, with the inland port of Miritituba in the state of Pará to the north. From there, the freight is to be shipped via the Tapajós and Amazon rivers to the Atlantic seaports and then to the world. The goals are to save transport costs and increase competitiveness. Proponents of the giant infrastructure project argue that the reduced freight costs would boost the growth of the Brazilian economy and relieve traffic on the roads. The railway thereby would replace the many trucks that currently still transport 70 percent of the harvest from Mato Grosso to the inland ports of Santos and Paranaguá, 2,000 kilometers to the south.

The Ferrogrão is intended to promote the production of soy and other agricultural commodities. By 2030, Mato Grosso is to increase its grain production, mainly for export, by 70 percent. Cultivation is expected to spread along the planned railway line. As a result, cattle pastures along the line would move into forest areas. A study conducted by the Climate Policy Initiative and the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio) estimates that the expansion of agricultural land in Mato Grosso promoted by the construction of the railway could directly contribute to the deforestation of more than 2,000 km² of natural forests - roughly equivalent to 285,000 football fields. The expansion of industrial agriculture would be accompanied by further loss of biodiversity and the additional exacerbation of illegal land grabbing, forest fires and the displacement of traditional populations from the region.

For the construction of the Ferrogrão, the protected status of an 862-hectare area of the Jamanxim National Park was already provisionally revoked in 2016 by back then President Michel Temer. This unconstitutional step prompted a judge of the Federal Supreme Court to temporarily suspend the construction permit. The project is currently being audited by the Federal Court of Accounts and the public-private partnership project is to be put out to tender in early 2022.

The Brazilian government presents the Ferrogrão as environmentally sustainable. The Ministry of Infrastructure argues that by shifting transport from trucks to train, CO2 emissions will be reduced by up to 1 million tonnes. The crucial miscalculation behind this: Forest areas that would be cleared for the Ferrogrão were not included in the equation. Clearing land to build the railway line would increase carbon emissions by 75 million tonnes - more than Austria produced in the whole of 2019.

People affected by the railway project are not consulted

The railway project would affect 16 indigenous territories of the Munduruku, Panará, Kayapó and Xingu peoples. Since the announcement of the project, the indigenous people living in the states of Pará and Mato Grosso have therefore been demanding a say and accurate information about the impacts of the rail project. And that is their right. After all, Brazil has signed the International Labour Organisation's Convention 169 on the Protection of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. This obliges Brazil to carry out free, prior and informed consultation with indigenous and other traditional peoples before approving large-scale projects. This is to allow indigenous peoples and other traditional communities to influence the design of the project and measures to avoid, mitigate and compensate for socio-environmental impacts. However, the people affected by the construction of the railway line were not consulted during the planning phase and the government confirmed that it will not carry out any prior consultations before tendering the licensing of the railway project. Jair Bolsonaro is also seeking to withdraw from ILO 169.

Can the EU still stop the grain train?

No. Brazilian soy as feed for the EU's industrial livestock sector will be transported on the Ferrogrão from Mato Grosso to the seaports, if the railway line is built. However, what policy instruments the EU could use to ensure that no new natural forests have been cleared to produce its imported agricultural goods is the subject of our policy analysis, which we intend to publish beginning of 2022. We examined two key pieces of legislation that are currently being developed at the EU level to ensure the respect of human rights and deforestation free supply chains. One is the Sustainable Corporate Governance Directive that intends to oblige companies across sectors to exercise due diligence with regard to the environment and human rights. The second piece of legislation would allow forest risk products such as soy, beef, palm oil or coffee, which are highly linked to deforestation, to be imported into the EU only if they meet certain sustainability criteria. We are also examining the extent to which red lines can be drawn in EU trade agreements that only allow trade with countries that have signed up to international human rights conventions and comply with sustainability criteria. We are also analyzing whether stricter social and ecological investment criteria can initiate more sustainable processes in countries of cultivation and production. Last but not least, we would like to follow the advice of our interview partners and contribute to international attention in order to increase the pressure on all actors involved to set the course for infrastructure projects in the interest of the people affected and the protection of the environment.

Our engagement for sustainable agricultural supply chains that protect the environment and human rights is supported by the Robert Bosch Stiftung.