As part of the European Green Deal, the European Union has committed to making European product markets more sustainable, with circularity playing a key role. The EU has therefore pledged to make sustainable products the norm in the EU, boost circular business models, and empower consumers for the green transition.

Throughout its life cycle, a product goes through many stages: it could be repaired, refurbished, or reused by a second user, and if that is not possible, its materials can be recycled. Comprehensive product information is key to the implementation of a circular economy: if detailed repair instructions are available, for example, it is easier to repair goods. For effective recycling, on the other hand, it is necessary to know the materials of a product.

As part of the currently negotiated Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR), the EU is therefore planning to introduce a Digital Product Passport (DPP) for a wide range of products. The DPP can be compared to a comprehensive digital index card or the digital CV of a product, with the primary aim of transferring information along its entire value chain. To pave the way for a circular economy, it should contain relevant data for all of the stages of the value chain of the product.

To date, the specific information to be included in the DPP has yet to be defined in the European legislative process. While the ESPR sets the framework of the DPP, the European Commission will define the details in so-called delegated acts separately for each product group. Ideas that are currently debated include the disclosure of information on production stages and economic operators, material composition, the carbon footprint, technical parameters, or detailed repair instructions.

Info Box: Circular Economy

Circular Economy is more than just recycling. It is a social and economic concept that aims to reduce the demand for primary resources and the negative impacts of current production and consumption patterns on climate, the environment, and human rights. It can be summarised by the 10 ‘R’ principles (see Potting et al. 2017):

- Refuse

- Rethink

- Reduce

- Reuse

- Repair

- Refurbish

- Remanufacture

- Repurpose

- Recycle

- Recover

The DPP is particularly relevant to the processes of reusing, repairing, refurbishing, remanufacturing, repurposing, and recycling:

While the concepts of reuse and repair are fairly clear, the other processes may require some further explanation:

Refurbish means improving old products to make them up-to-date and easy to reuse.

Remanufacture refers to using components from broken products for new products.

Repurpose aims to use components from defective products for other purposes for which they are still suitable.

Finally, recycling is the process of recovering materials from old products for reuse as secondary raw materials.

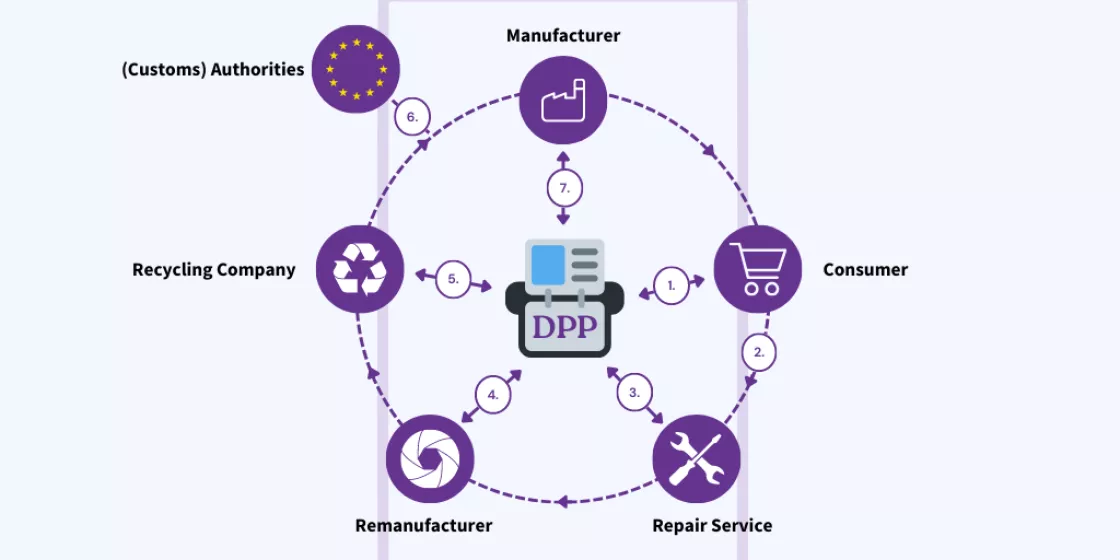

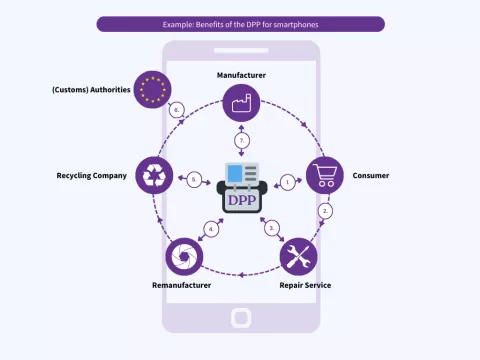

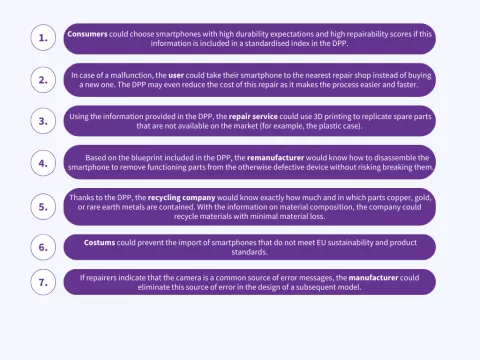

Properly designed, the DPP can provide valuable information to various actors along the value chain or life cycle of a product. Among other things, the information can be used to…

... enable manufacturers to optimise their products in terms of material and energy efficiency.

... help consumers/users to make informed purchasing decisions, to use the products longer, and to dispose of them properly.

... make the work of operators offering services to repair, refurbish, remanufacture, and repurpose products easier and their business models more profitable.

... enable recycling companies and raw material producers to keep materials of the highest value in the cycle.

... allow waste management companies to dispose of products properly.

In addition, the DPP offers opportunities for actors operating outside the life cycle or value chain of a product. For example, the DPP can be a valuable tool for compliance and sanctioning authorities to verify product standards and a company’s efforts to implement human rights and environmental due diligence.

In the future, the DPP could foster new market opportunities for business models that strengthen the circular economy. Until now, it has been difficult for companies to take action on repurposing individual components of a product because they do not know how long a component has been in use or how well it performs and is stable. With the help of a DPP, repurposing could become the subject of new business models. The collected information will also allow legislative authorities to introduce new product regulations and/or adapt existing ones. In addition, the data will enable civil society actors and academia to critically examine current regulations and provide input for adjustments.

In our policy paper The Digital Product Passport, we argue that the full potential of the DPP should be unlocked to make it a game changer for the circular economy and the absolute reduction of resource consumption. Therefore, the DPP must be designed in such a way that it is particularly empowering for actors in the fields of product life cycle extension.

In general, we recommend that:

- the DPP must provide information to implement the hierarchy of the 10 ‘Rs’ of a holistic circular economy;

- relevant information must be accessible to the relevant actors along the value chain; and

- the DPP system itself, that is, the digital infrastructure behind the passport, must consume as little energy and resources as possible.

The DPP must therefore meet the following criteria:

- The obligation to disclose information in the DPP must apply to all products that are not easily prepared for reuse or recycling in order to realise the DPP’s full potential impact;

- The ESPR must set out mandatory information requirements. Some information requirements, such as repair instructions or material composition, should be mandatory for all products. They should not be negotiated for each specific product group;

- The information included in the DPP must be standardised so that actors along the entire value chain and across sectors can easily read and use them;

- Information requirements should focus not only on recycling but also on other circular economy processes such as repair or remanufacturing. Otherwise, the DPP may contribute to disregarding the circular economy hierarchy by making recycling more economically attractive than other processes of the circular economy;

- In line with yet to be defined access regulations, information relevant to repair, refurbishment, recycling, and other processes of the circular economy must be available to all relevant actors along the value chain, including those operating independently of manufacturers and outside of the EU. This is key to facilitating a decentralised circular economy and preventing the transition to a circular economy from contributing to a monopolisation of value creation;

- The DPP system itself must be designed to be as resource and energy efficient as possible to avoid the resource and energy intensity of the system outweighing the potential savings made possible by the DPP.

The discussion on the DPP may still be in its early stages, but the relevant framework conditions are being set at this moment. We therefore advocate taking action now to make the DPP a game changer for the circular economy.